Art as Witness to Climate Crimes

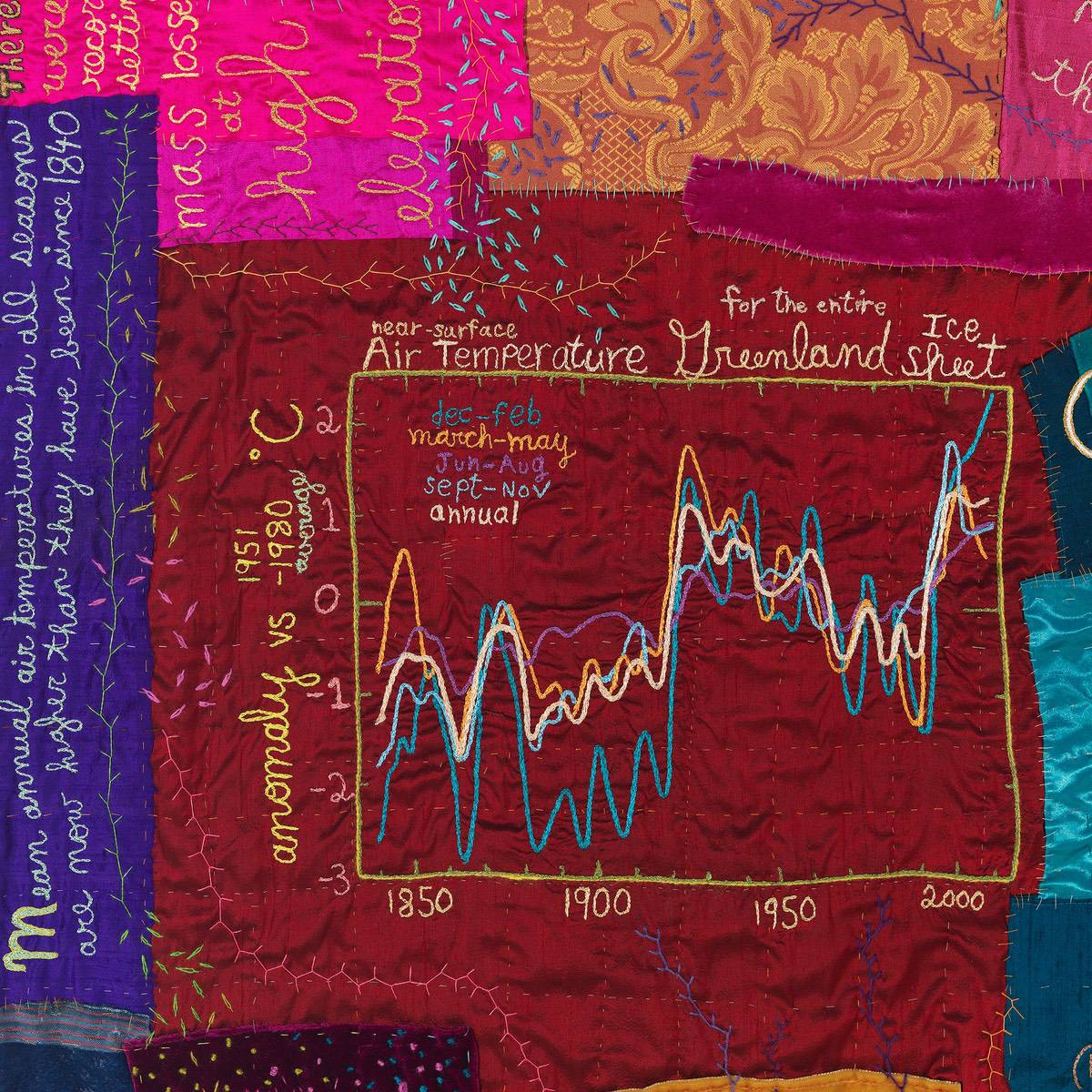

Two textile artists respond to climate collapse with needle and thread — one embroiders glacier data onto silk, the other gathers strangers in a library basement to make a crazy quilt from surgical bandages and childhood dish towels.

In Michigan, Bonnie Peterson embroiders climate data onto silk. In Minneapolis, Shug Munich gathers strangers to make a "crazy quilt" from surgical bandages and childhood dish towels. Both are working with their hands to witness something most of us struggle to look at directly — the unraveling of our planet's climate.

This isn't new. Artists have always been among the first to witness what empires refuse to see. But the story of environmental art in the developed world is also the story of what richer nations forget — or refuse to learn. Before Western environmentalism had a name, Indigenous peoples across what's now called North America had been practicing environmental stewardship for millennia.

"I'm Bonnie Peterson and I am in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan near the south shore of Lake Superior... Lake Superior is one of the biggest surface areas of any lake in the globe. So people are a little concerned about it, which is nice. And I'm making climate graphs with embroidery and climate change is my passion right now."

— Bonnie Peterson, Climate Data Embroiderer

Bonnie's work transforms scientific data into objects that can be held, contemplated, and passed down. She cold-emails glaciologists and fire scientists, asking them to explain their research until she understands it — then spends months or years translating that data into embroidery on silk. Her fire science piece, showing the complex relationships between drought, temperature, and wildfire, demands that viewers stop, read, and understand.

"Each artist is being asked to facilitate some sort of project that responds to climate collapse and hopefully engages community into building some climate resistance... How are we engaging in community so that you're not holding this alone?"

— Shug Munich, Textile Artist & Community Facilitator

Quilting Amidst Collapse

Shug Munich's project, "Devotion Is Never a Waste: Quilting Amidst Collapse," invites people to bring fabric that would otherwise be thrown away and transform it into a crazy quilt. The materials people bring carry stories: owl-print pillowcases from a grandmother's house, dish towels from a childhood cabin, post top-surgery bandages.

Climate grief is isolating. The scale of the problem makes individual action feel pointless. That's exactly where community craft becomes essential. As Shug puts it: there's so much waste around us, and it feels a lot more possible to figure out what to do with that waste if you're not doing it alone.

"The things that I've made, historically, have had a kind of dually dystopian and utopian sort of vision... dystopian in the sense that they're more or less 100 percent constructed from the refuse of society, that they respond to what's now termed the Anthropocene, this sense that we're literally drowning in plastic and trash."

— Paul Yore, Australian Artist

Data Under Attack

Bonnie is developing contingency plans to keep accessing climate data by switching to European databases like Copernicus because her own government might erase the information. This is what bearing witness looks like now — a fiber artist in Michigan, tracking which universities are picking up data collection as federal agencies are defunded.

Down in a library basement, Shug leads people through the slow work of cutting and stitching while the world walks by overhead. People peeking through the basement windows asked the librarian: "What's going on? People are smiling. How do I do that? I want to sew."

This is what artists have always done. They find the basement. They find the margins. And they make something there that outlasts the empires walking overhead.

Gallery

Bonnie Peterson, Turning Green (detail), 2013. 81cm x 132cm (32″ x 52″). Appliqué, hand and free motion embroidery. Silk, velvet, brocade, threads.

Shug Munich, Quilting Amidst Collapse community quilt. View project →